STEPAN BANDERA: “...ideological and moral principles will never allow Ukraine to become an accomplice of Moscow...”

Author: Alik Gomelsky

The leader of the Ukrainian national independence movement lived a relatively short life, spending over nine years in total under arrest. In 1959, at the age of 50, he was assassinated in Munich by a Soviet killer, Bohdan Stashynsky. More than 60 years have passed since then, yet the name of Stepan Bandera continues to stir the minds of historians, political scientists, philosophers, and writers. His figure compels politicians and propagandists to work tirelessly, repeatedly invoking his name and legacy.

When I was writing a book about Jewish–Ukrainian relations, I had the opportunity to explore and uncover facts about this national leader. I wrote about him a relatively brief (especially compared to the materials on Symon Petliura or Yaroslav Stetsko) yet substantial piece, supported by archival documents as well as examples of Soviet propaganda clichés.

Recent publications and interviews by historians such as Rossolinski-Liebe, Hrytsak, Zaitsev, and Solonin—not to mention public figures like Gozman or Shenderovich—prompted me to write this article, in an attempt to separate truth from falsehood, and the man from the symbol.

Let me begin with a quote from Stepan Bandera’s writings:

“...The striving for freedom and truth, a sense of justice, and a high idealism were—and have always remained—the fundamental principles of the Ukrainian people and the Ukrainian individual, the main driving forces of Ukrainian existence and Ukrainian spirituality. Our people always yearn for freedom for themselves and wish it for other nations. They fight and struggle for truth and justice. We want to live in harmony and mutual respect with all peoples of goodwill. We recognize the same rights for other nations that we fight for ourselves. We do not want to be either the object or the cause of enslavement and injustice. We actively fight for freedom and truth not only because we need them for ourselves, but above all because God gave these treasures and laws to humanity, and the foundation of our will is to follow God's will. Such ideological and moral principles will never allow Ukraine to become an accomplice of Moscow in its anti-popular, aggressive imperialism...”.

Stepan Bandera.

Let’s examine a few statements.

For example, after his interview was published in Le Monde, historian Yaroslav Hrytsak wrote an article for Istorychna Pravda (Historical Truth), in which he said:

...I said that even the work of Volodymyr Viatrovych as director of the Institute of National Memory did not change much in this regard. He and his colleagues attempted to create a positive image of the Bandera movement, which they claimed was not involved in the killings of Poles and Jews. But their efforts changed very little... None of the Ukrainians who speak about Bandera today intend to kill Poles or Jews—although in Polish, German, and Jewish historical memory, Bandera is seen as a person associated with the murder of Poles and Jews...

Regarding Bandera’s participation in the killings of Poles and Jews, I repeated my usual answer: he is accused of crimes he did not commit, and credited with exploits he had nothing to do with...

Furthermore, we must consider that the young Bandera was a silent leader—a man of action rather than words—so we don’t know exactly what his views toward Jews and Poles were at the time, nor can we say what he would have done had he not been imprisoned during the war...

There is no doubt that Banderites killed Poles and Jews...

It is also unclear to what extent Bandera was involved in the creation of the Banderite Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA)...

Source:

https://www.istpravda.com.ua/columns/2023/01/14/162284/

– Based on these statements, we can conclude that, in historian Hrytsak’s view, the Banderites were certainly involved in the killings of Jews and Poles, although Bandera himself did not personally take part in these crimes. However, Hrytsak is unsure of the OUN(B) leader’s personal views on Jews and Poles, or what actions Bandera might have taken had he not been imprisoned during the war.

It is also unclear to the historian whether Bandera played a role in the creation of the "Banderite UPA." Whether Hrytsak was in a hurry to write an excuse, or simply was not in the mood, it’s difficult to follow the twists and turns of his statements. This raises further questions: Did he even study the documents of the 2nd Congress of the OUN(B) (April 1941)? And how exactly does he imagine Bandera’s participation in the creation of the UPA—when Stepan Bandera himself was at that time imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp?

Page of political resolutions of the 2nd Congress of the OUN(B), April 1941.

The answer to these questions was given by the previously mentioned Volodymyr Viatrovych in his response article to Hrytsak:

“...It’s surprising to hear such confident statements from someone who, as a researcher, has never actually studied either the real Bandera or the movement he led. After all, in his own article for Istorychna Pravda, he repeatedly says 'unknown' when it comes to key moments in the history of this movement.

It’s true that many aspects of Bandera’s biography remain unexplored. And Professor Hrytsak is in no rush to join the ranks of historians who are working with archival materials to reduce the number of such blank spots...

It’s worth noting the rare instance of Hrytsak referring to a primary source—but how much can the personal opinion of a female courier truly demonstrate the position of the UPA leadership toward Bandera?

The heated discussion surrounding the publication even inspired some Ukrainians to propose forming a ‘Society for the Protection of Hrytsak,’ simply because he remained silent for a few days and didn’t engage in the debate.

Yet no one proposes forming a society for the protection of Bandera—slandered for decades by Polish, German, Soviet, and Russian propaganda—who has remained silent since 1959 and can no longer speak for himself...”

Source: https://www.istpravda.com.ua/columns/2023/01/16/162285/

International columnist Yefim Fistein wrote in his column for Radio Liberty:

...Philosophers have noted that the true embodiment of ‘Ukrainianness’ was not the selfless Stepan Bandera, not the bespectacled academic Mykhailo Hrushevsky, head of the Central Rada, not the quick-tongued journalist Symon Petliura, and certainly not the ragtag ataman-turned-hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky—who, in reality, was a noble-born Polish szlachta, not a vagabond—but rather Nestor Makhno: a self-taught polymath, a committed autonomist, a spontaneous practicing anarchist, and an early proponent of decentralized social self-organization.

He became the embodiment of the Ukrainian spirit, which some interpret as the untamed force of Cossack freedom (not for nothing, he was born in the village of Huliaipole), and others as the incarnation of an indomitable love of freedom...

Source: https://www.svoboda.org/a/stihiynyy-otbor-efim-fishteyn---ob-ukrainskom-vospriyatii-mira/32225696.html

The Ukrainian leaders of the 20th century mentioned by Yefim Fistein (Bandera, Hrushevsky, Petliura, Skoropadsky, Makhno) are ones I’ve studied in depth—particularly Symon Petliura and Stepan Bandera.

To call Petliura a “quick-tongued journalist” can only be said by someone who has a very superficial understanding of Petliura’s thinking, political strategy, and actions. As for Nestor Makhno, far fewer people followed him than followed the Ukrainian People’s Republic under Petliura—or, of course, the OUN(B) under Bandera. That is precisely why it was Petliura who was assassinated in Paris, and Bandera in Munich—not Makhno.

The spirit of Ukrainian defiance and action was most fully embodied by Bandera—described by Fistein, whether ironically or not, as “selfless.” I know firsthand—through direct sources—how, when, and by whom officers of the Armed Forces of Ukraine were trained in small-unit tactics and grassroots command initiative in the lead-up to Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. These tactics have proven highly effective in the ongoing war

But Ukrainians understand discipline—they simply do not view their commanders and leaders as masters, gods, or tsars, unlike their northern neighbours. Hence the overthrow of Skoropadsky, the split within the OUN, and the Revolution of Dignity. Even President Zelensky, despite being in the global spotlight, is regarded by many as merely the latest crisis manager in Ukraine.

Source: https://www.svoboda.org/a/stihiynyy-otbor-efim-fishteyn---ob-ukrainskom-vospriyatii-mira/32225696.html

Symon Petlijura.

Historian Oleksandr Zaitsev, in an interview with the pro-Ukrainian Israeli radio station Best Radio, expressed the opinion that Bandera did not pose a real threat to the USSR, making it unclear why he was assassinated in West Germany in 1959.

The philosopher Oleksiy Panych offered an interesting perspective on questions of history and historical memory:

...3. Western left-liberal historians (such as John-Paul Himka, Per Anders Rudling, or Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe) engage in incorrect and manipulative context-blending when they try to impose their vision of Bandera, the OUN, and the UPA—framed within the ‘critical history’ of European far-right movements—onto contemporary Ukrainians, who now, more than ever, need the figure of Bandera in the context of Ukrainian national ‘monumental history.’

4. But it would also be pointless for Ukrainian historians to expect the Western public—let alone these professional ‘anti-fascist historians’—to widely accept the prevailing Ukrainian perspective on Bandera...

Source: https://www.istpravda.com.ua/columns/2023/01/17/162295/

In my view, the key question is this: Should Ukrainians be ashamed of Stepan Bandera and his actions? To answer that, let’s begin by examining some of the most common claims. Here we go:

Claim: Stepan Bandera was not a theorist—he was illiterate (a bumpkin, redneck, etc.).

This is a direct repetition of the Soviet propaganda narrative that Ukrainians are “illiterate peasants, even if their songs are nice.” In fact, similar derogatory narratives still persist about other peoples of the former Soviet Union.

True, Stepan Bandera wasn’t formally trained as a philosopher—he was a man of action who revitalized the Ukrainian nationalist movement. But that does not mean he didn’t engage with ideology or strategy. The son of a member of parliament in the Western Ukrainian People's Republic (ZUNR) and the nephew and grandson of priests, Bandera grew up in an atmosphere of Ukrainian national revival. He successfully completed gymnasium and aspired to become an agronomist, but political discrimination against ethnic Ukrainians in Poland prevented him from obtaining a degree at the Agricultural Academy in Czechoslovakia. Later, he was barred from completing his thesis defense at the National University "Lviv Polytechnic," despite completing the full course of study.

Bandera lived a short but active intellectual life. During his many years in prisons and concentration camps, he was forbidden to write. He could only reflect—always uncertain if his thoughts, ideas, and plans would ever come to fruition.

Claim: Bandera killed Poles.

This accusation is based on the fact that Bandera was sentenced to death in Poland for involvement in the planning and leadership of the assassination of Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki—who oversaw the so-called “pacification” campaigns (i.e., violent police and military actions against Ukrainian civilians in the Polish Republic). Bandera was arrested the day before the assassination and later sentenced to death, which was altered to life imprisonment. The outbreak of World War II cut his prison term short.

However, in July 1941, Bandera was arrested by the Nazis for proclaiming Ukrainian independence. So, the only Pole whose murder Bandera was associated with was a government official directly responsible for violent repression against ethnic Ukrainian civilians.

A particularly revealing document is the political resolution adopted at the 2nd Congress of the OUN(B) in April 1941. Specifically, Point 16 states:

“The elimination of anti-Ukrainian actions by the Poles is a prerequisite for the normalization of relations between the Ukrainian and Polish nations.”

Claim: Bandera killed Jews.

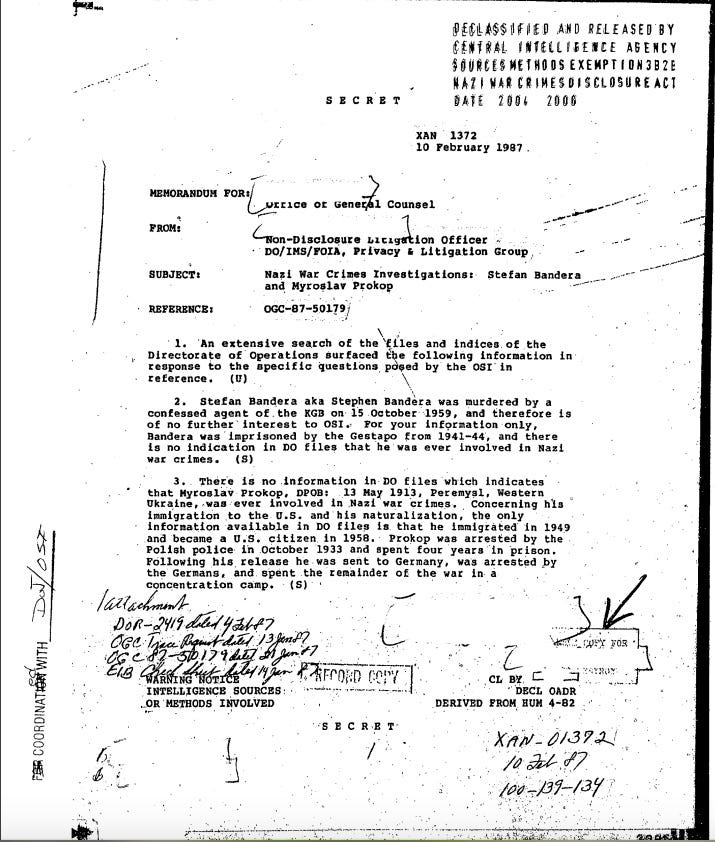

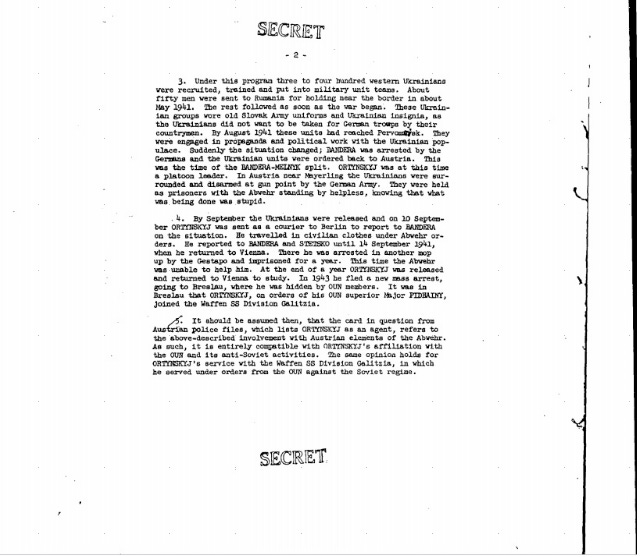

According to declassified CIA documents, Stepan Bandera had no involvement in the Shoah (aka Holocaust) or other Nazi crimes.

It may sound absurd, but some Russian-speaking critics of Bandera claim that, although he was in Nazi custody from July 1941 to the fall of 1944, the Nazis “released him at night so he could go kill Jews.” No comment.

Bandera never issued orders to kill Jews, nor did he organize pogroms. Those who accuse him of antisemitism or complicity in the Shoah have yet to present any evidence.

Claim: Bandera lacked popularity and significance; he posed no real threat to the USSR, and it was only his assassination—ordered by Nikita Khrushchev—that made him a hero and martyr.

A further development of this claim is the argument that if Bandera had truly been the leader of the Ukrainian resistance and the main symbol of the struggle against Moscow, he would have been eliminated long before 1959. Therefore, it is more likely the opposite—Stepan Bandera’s activities supposedly created division and weakened the liberation movement.

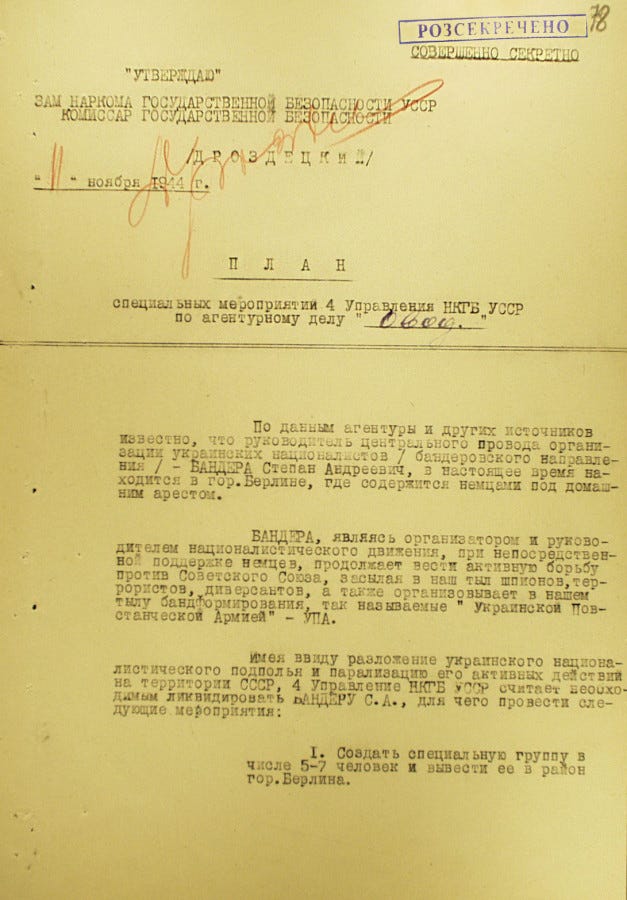

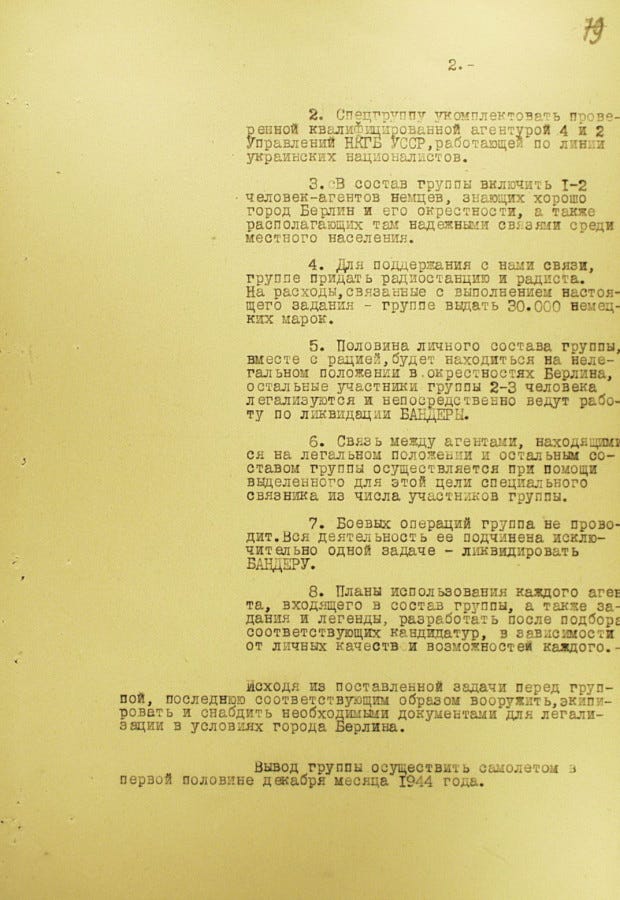

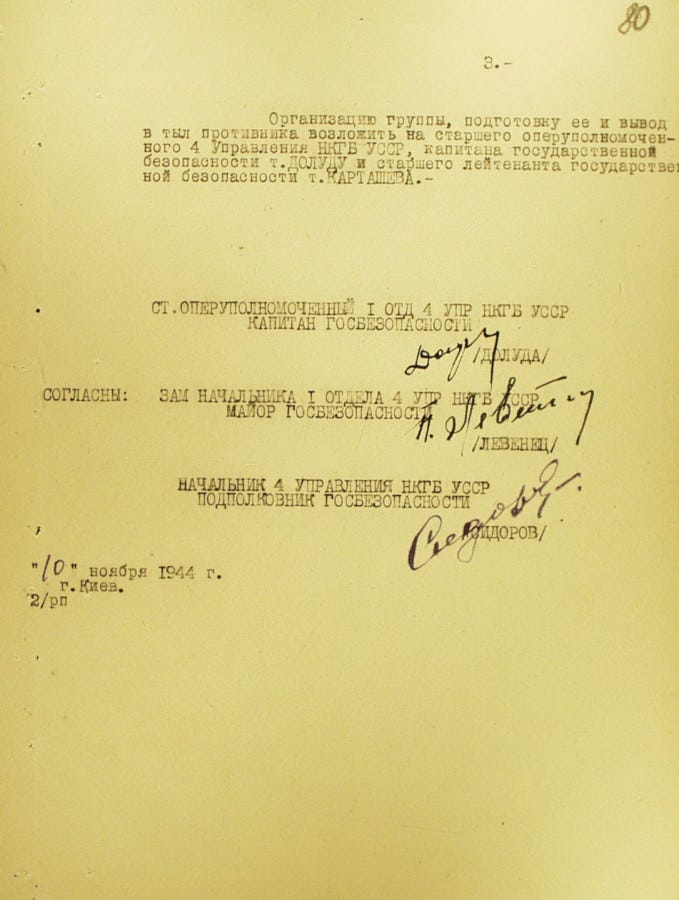

These claims are entirely refuted by recently declassified KGB archives released by the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine. One of the documents describes preparations for an operation codenamed “Ovod” (“Gadfly”) to deploy a special group of 5–7 operatives into the Berlin area. The group was to include 1–2 German agents familiar with the terrain and possessing local contacts. The unit was equipped with a radio station, a radio operator, and 30,000 marks in cash. Half of the group was to be “legalized” (operating under official cover), while the other half would remain in hiding. Their sole mission: assassinate Stepan Bandera. The operation was to be carried out via airdrop.

The most important detail: the document is dated November 10, 1944. In other words, the leader of the OUN(B) was considered such a serious threat to the USSR that, during World War II, special forces, agents, and resources were allocated for his targeted elimination.

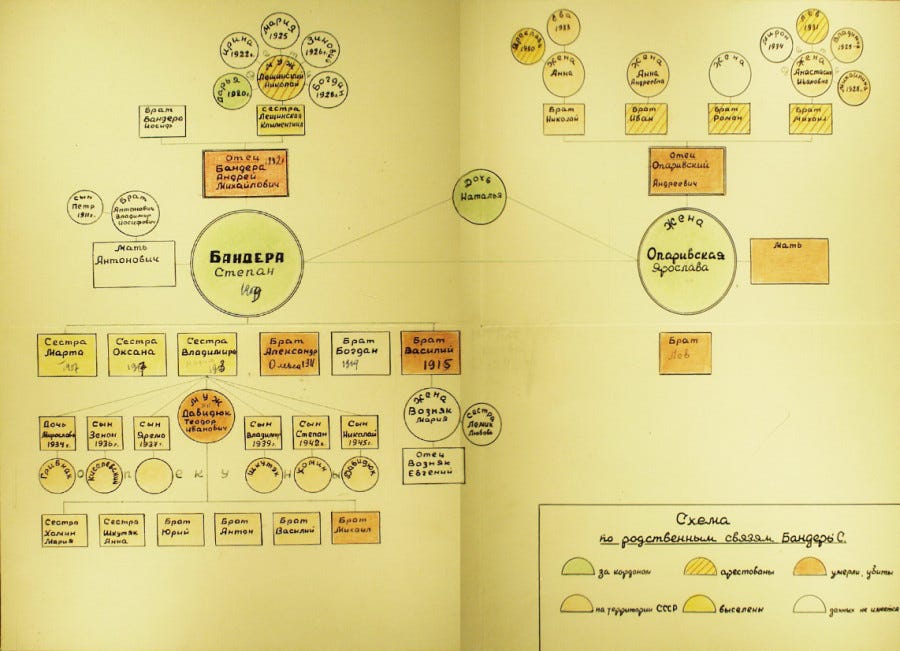

Interestingly, the same archive folder contains documents dated 1940 and 1941 related to Stepan Bandera. These note that in January 1940, Bandera was negotiating with the Italian government to obtain arms and have them transported to Ukraine. The folder also includes a genealogical chart of Bandera’s family. One notable detail: the document was annotated to show which of his relatives were arrested, dead or killed, or deported by Soviets and Nazis.

And one more point: if, as his critics claim, Stepan Bandera truly “sowed division and weakened the liberation movement,” then Moscow should have treated him as a valuable asset, preserving and supporting him to help fracture the movement. Instead, they assassinated him—thus uniting Ukrainians and eliminating internal divisions.

From the KGB archives: A document detailing preparations for an operation codenamed “Ovod” to assassinate Stepan Bandera in Berlin.

November–December 1944.

From the KGB archives: Documents dated 1940 and 1941 concerning Stepan Bandera.

Note the signature of Pavel Sudoplatov on the 1940 document.

From the KGB archives: Stepan Bandera’s family tree compiled by the NKVD.

Claim: Bandera was a tyrant and dictator.

– In what way exactly did this dictatorship manifest? Did he eliminate political rivals? Ban political parties? Carry out ethnic cleansing? Did he establish concentration camps for his opponents? Hypothetical speculation doesn’t work here.

Claim: Bandera stole money from the Abwehr.

– This accusation indirectly confirms that Stepan Bandera was in contact with the Abwehr. But it’s important to note that the Abwehr was meticulous—typically German—in handling internal misconduct. For example, Abwehr officer Oskar Schindler (yes, the same one recognized as Righteous Among the Nations) was sent to Turkey to investigate financial fraud among officers of the Reich’s intelligence service.

If Bandera had in fact, committed financial misconduct, documents investigating such behavior would almost certainly have surfaced—if not after July 20, 1944, then certainly during the Nuremberg Trials.

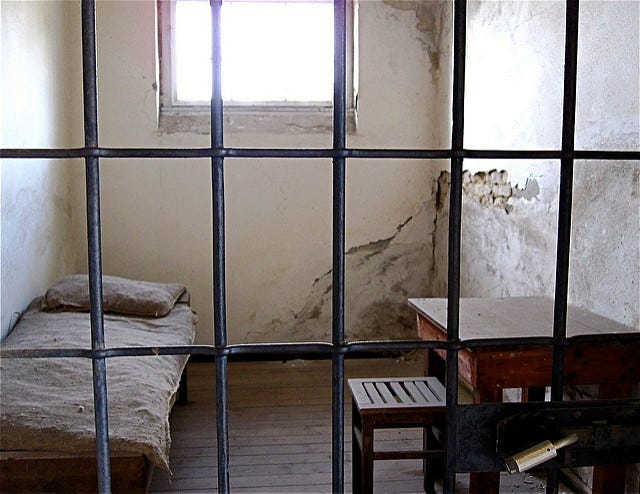

Claim: Bandera lived in comfort while imprisoned by the Nazis.

– Unfortunately, the Soviet agitprop myth that Bandera’s imprisonment in the Zellenbau block of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp was something like a resort is still enthusiastically spread today by both Putinist propagandists and members of the so-called Russian liberal opposition, such as historian Mark Solonin.

But a closer look at the actual conditions of confinement, the fates of other inmates in that block (for example, the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Home Army, Stefan Rowecki, and one of the leaders of OUN(M), Oleh Olzhych), and the fates of Bandera’s own family members reveals the harsh reality. For illustration, here are details about the fate of his relatives:

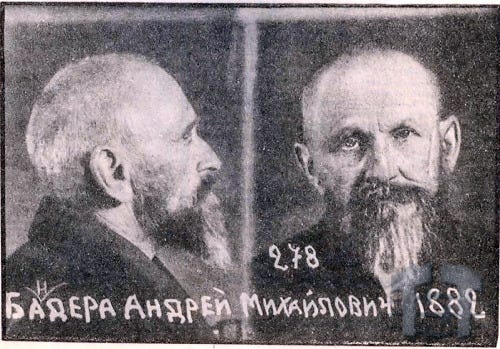

Father Andriy Bandera – a staunch supporter of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic and a chaplain in the Ukrainian Galician Army, was executed by order of an NKVD tribunal (according to some sources, he was crucified, since he was a priest of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church) on July 10, 1941.

Brother Oleksandr – was imprisoned in Auschwitz on July 22, 1942, where he died from torture (possibly at the hands of Volksdeutsche guards); his body was cremated.

Brother Vasyl – was arrested in September 1941, spent a long time in prison, and was sent to Auschwitz in July 1942, where he also died (possibly beaten to death).

Sister Volodymyra – sentenced in 1946 (in the USSR) to 10 years in a forced labor camp and 5 years of loss of civil rights, along with confiscation of property. Her six children were sent to orphanages.

Sister Marta-Maria – from May 1941 to March 1960, she was imprisoned (in jails, camps, and special settlements in the Krasnoyarsk region). Even after release, she was not permitted to return to Ukraine.

Sister Oksana – from May 1941 to February 1960, she was also imprisoned (in jails, camps, and special settlements in the Krasnoyarsk region). She, too, was banned from returning to Ukraine after her release.

Stefan Rowecki, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa).

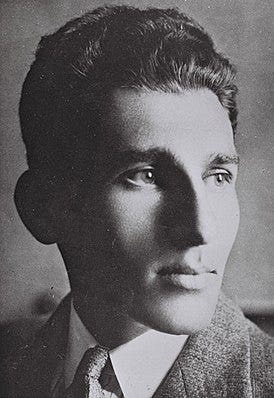

Stepan Bandera, Chief of OUN(B).

’Resort’ cell in the Zellenbau block.

A caricature of Stepan Bandera (from Soviet Agitprop).

Andriy Bandera (father of Stepan Bandera). Photo from NKVD archives.

Claim: Bandera collaborated with fascists/Nazis.

We find compelling insights when we examine the circles in Germany with whom Bandera and other members of the OUN(B) were in contact and collaboration. As it turns out, most of these figures belonged to the Abwehr and Wehrmacht—organizations that were not designated as criminal (unlike the SS, SD, or Gestapo), and many of whose members were involved in anti-Hitler conspiracies.

Most importantly, Bandera did not seek to annex foreign territory, as was done by Nazi Germany’s ally, Stalin’s USSR. Bandera’s aim was Ukrainian independence—a goal that, interestingly, the Abwehr and Wehrmacht were relatively sympathetic toward. There are documents indicating that German military officers warned the OUN(B) in advance about planned SD and Gestapo reprisals against the organization’s leadership, following the declaration of Ukrainian independence on June 30, 1941.

Note on Erwin Lahousen von Vivremont:

Erwin Lahousen von Vivremont, an Austrian aristocrat, served in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. After Austria’s annexation into the German Reich, he joined the Abwehr as an officer in Austrian counterintelligence. Lahousen, a major general, headed the Abwehr’s 2nd Division and was one of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris’s closest allies in many plots to overpower Hitler. He was directly involved in several anti-Hitler conspiracies, including the July 20, 1944 plot.

Under Lahousen’s command was the "Brandenburg-800" regiment (later a division), which included the "Nachtigall" Battalion made up of Ukrainians—its Ukrainian commander was Roman Shukhevych. Lahousen escaped Gestapo reprisals only because he had been stationed on the Eastern Front since 1943. After the war, he became one of the chief prosecution witnesses at the Nuremberg Trials.

It’s important to note, as confirmed by recently declassified CIA archives, that the training and deployment of the "Nachtigall" and "Roland" Battalions were conducted by the Abwehr in secret—not only from the SS and SD, but even from the Nazi Party (NSDAP) itself.

Erwin Lahousen von Vivremont.

ABN. Yaroslav Stetsko (standing), his wife Slava (seated on the left).

Claim: Ukrainians had criminals like Bandera and Shukhevych, and Russians had Stalin.

Is it appropriate to compare Stalin, the leader of the USSR—personally responsible for the deaths of millions, the creator of an unprecedented system of concentration camps (the GULAG), one of the initiators of World War II, and the conqueror of much of Europe—with Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, who fought for the survival of their own people and were themselves prisoners of camps and prisons?

This question is rhetorical.

Such comparisons reveal the historical ignorance of so-called Russian democratic opposition members—many of whom, until recently, tried to make deals with the Putin regime and continue to play by its rules.

Roman Shukhevych.

In one of my books, while writing about the heroes of the Jewish national independence movement, I drew parallels between Stepan Bandera and the Zionist Avraham Stern:

Stepan Bandera was never a citizen of Ukraine, and Avraham Stern was never a citizen of Israel.

Bandera took part in terrorist actions against the oppressors of the Ukrainian people; Stern carried out acts of terror against the oppressors of the Jewish people.

Stepan Bandera engaged with the Nazis in an effort to save the Ukrainian people; Avraham Stern did the same to save the Jewish people.

Bandera was killed by Soviet imperialists; Stern was killed by British imperialists.

Bandera fought for Ukraine’s independence from Muscovy, which had denied Ukrainians their freedom for centuries; Stern fought for Israel’s independence from Britain, which violated its obligations under the Palestine Mandate.

A town—Kokhav Ya’ir (Hebrew: כוכב יאיר, “Ya’ir’s Star”)—was named after Avraham Stern in 1981, as were streets in Tel Aviv (where he was killed) and other cities in Israel.

So why shouldn't streets and avenues in Ukraine be named after Stepan Bandera?

Avraam Stern.

I agree that we should not portray Stepan Bandera (or any other leader of a national liberation movement) as saintly—an infallible angel. They were all human, with their own weaknesses, misconceptions, and mistakes, alongside their principles and resilience.

It is crucial to understand that the heroes of one nation may be, and often are, anti-heroes for others:

Józef Piłsudski is an anti-hero for Ukrainians,

Avraham Stern, Menachem Begin, and Yitzhak Shamir are anti-heroes for Britain,

and Stepan Bandera is an anti-hero for Poland.

But to truly grasp the meaning of each historical figure and event, we must look at the entire picture, not just isolated fragments. Otherwise, our understanding becomes distorted, one-sided, and incomplete.

Yes, over the past nine years, Stepan Bandera has become one of the key symbols of the Ukrainian people’s steadfast struggle—a struggle shared by Ukrainians of various ethnic backgrounds—for life and freedom.

And so, at a time when Russia’s military machine is attempting to annihilate Ukraine and its people, efforts to undermine this symbol of resistance to genocide—by levying often contrived and baseless accusations against Bandera—bring us to the age-old question:

Cui prodest? Who benefits?

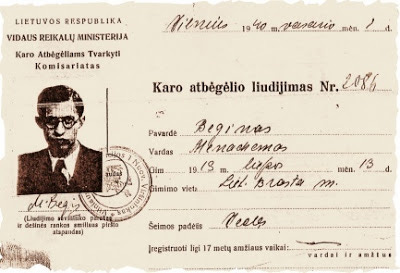

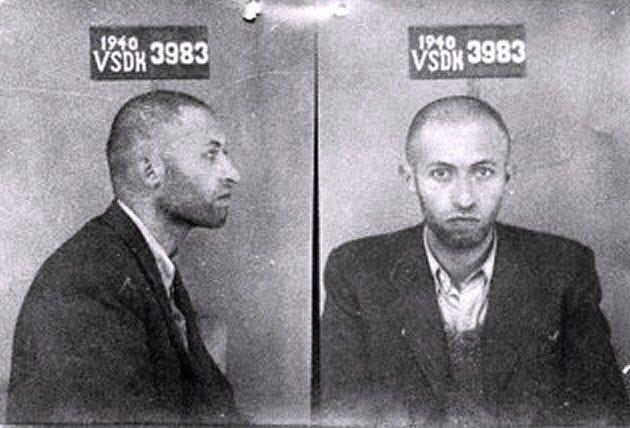

Documents and photographs of Menachem Begin from the NKVD.

Yitzhak Shamir and Margaret Thatcher. A very telling photograph—after all, Shamir was considered a terrorist and a murderer of British citizens.

Sources:

Stepan Bandera, "Perspectives of the Ukrainian Revolution", Vozrozhdenie, Drohobych, 1998 (reprint of the OUN edition, Munich, 1978)

Alik Gomelsky, "Jewish–Ukrainian Relations. 20th Century", Ukrainian Priority, Kyiv, 2021

Alik Gomelsky, "History. The Uncomfortable Truth", Ukrainian Priority, Kyiv, 2021